A common data science task is extracting data from a website. Many public-facing websites do not have a public facing API; one has to extract information from the HTML pages instead.

This document explores building a simple web spider and shows how its

performance can be improved using asynchronous processing. Along the way

is introduced the async and await operators

which allow you to write functions which can operate concurrently,

pausing and resuming as data become available.

A simple (synchronous) web spider

For a simple case, say you wanted to gather the graph of a site –

every URL linked to from every page. You could use the curl

package to fetch web pages, and the XML package to parse

the links out of their content. Without using any asynchronous

processing, a simple web spider might look like this:

First we have a helper function to extract a list of links from a downloaded web page.

extract_links <- function(data) {

(data$content

|> rawToChar()

|> XML::getHTMLLinks(externalOnly=TRUE)

|> vapply(FUN.VALUE="",

\(link) tryCatch(XML::getRelativeURL(link, data$url, addBase=TRUE),

error=\(e) NA_character_))

|> na.omit()

|> as.character())

}Then the meat of the task is covered in this function:

spider_site <- function(

start_pages, #starting URLs

regexp, # Linked URLs must match this to be included

limit=500) { # maximum number of pages to collect

#all encountered pages will be collected in this hash table

pages <- new.env()

# keep track of how many URLS seen and stop after a limit

seen <- 0

# inner helper function:

is_new_page <- function(url) {

is_new <- (seen < limit) && !exists(url, pages) && grepl(regexp, url)

if (is_new) {

#mark this page as "in progress" and increment counter

pages[[url]] <<- list()

seen <<- seen + 1

}

is_new

}

# define inner recursive function to visit a page

visit_page <- function(url) {

cat("visiting ", url, "\n")

# Fetch the page

start_time <- Sys.time()

data <- curl_fetch_memory(url)

end_time <- Sys.time()

# extract the links and store our page in the hash table.

links <- extract_links(data) |> unique()

pages[[url]] <- data.frame(

url = url, start = start_time, end = end_time, links = I(list(links)))

#recursively follow new links, if within the site filter

( links

|> Filter(f=is_new_page)

|> lapply(visit_page))

invisible(NULL)

}

# Kick off by visiting each page in the starting set.

start_pages |> lapply(visit_page)

#Return our hash table as a data frame with "links" as a list-column.

pages |> as.list() |> do.call(what=rbind)

}To narrate the above: The outer function spider_site

holds a hash table of all known pages, and that table is filled out by

calling inner function visit_page. In

visit_page we request and receive the web page, extract all

the links, and recursively follow any links that fall within the site

regexp – as long as those URLs haven’t been seen before

To spider a site, here, give it a starting function and a filtering regexp, like so:

spidered <- spider_site("https://mysite.example/webapp", "mysite\\.example/")

saveRDS(spidered, file="spidered.rds")(Since building packages should not perform a DDoS, the above is not run in the vignette; I’ve included an example dataset instead.

spidered <- readRDS("spidered.rds")The above spider is synchronous; when it requests a web

page, it waits for the entire page to be retrieved before continuing.

For curl_fetch_memory to return a value, it needs to open a

TCP connection to the remote server, send the request, wait for the

network to carry the request to the server; then the server must process

the request and send the result back over the network, then the client

must wait for the whole page to come over the network we can process a

list of links out of it.

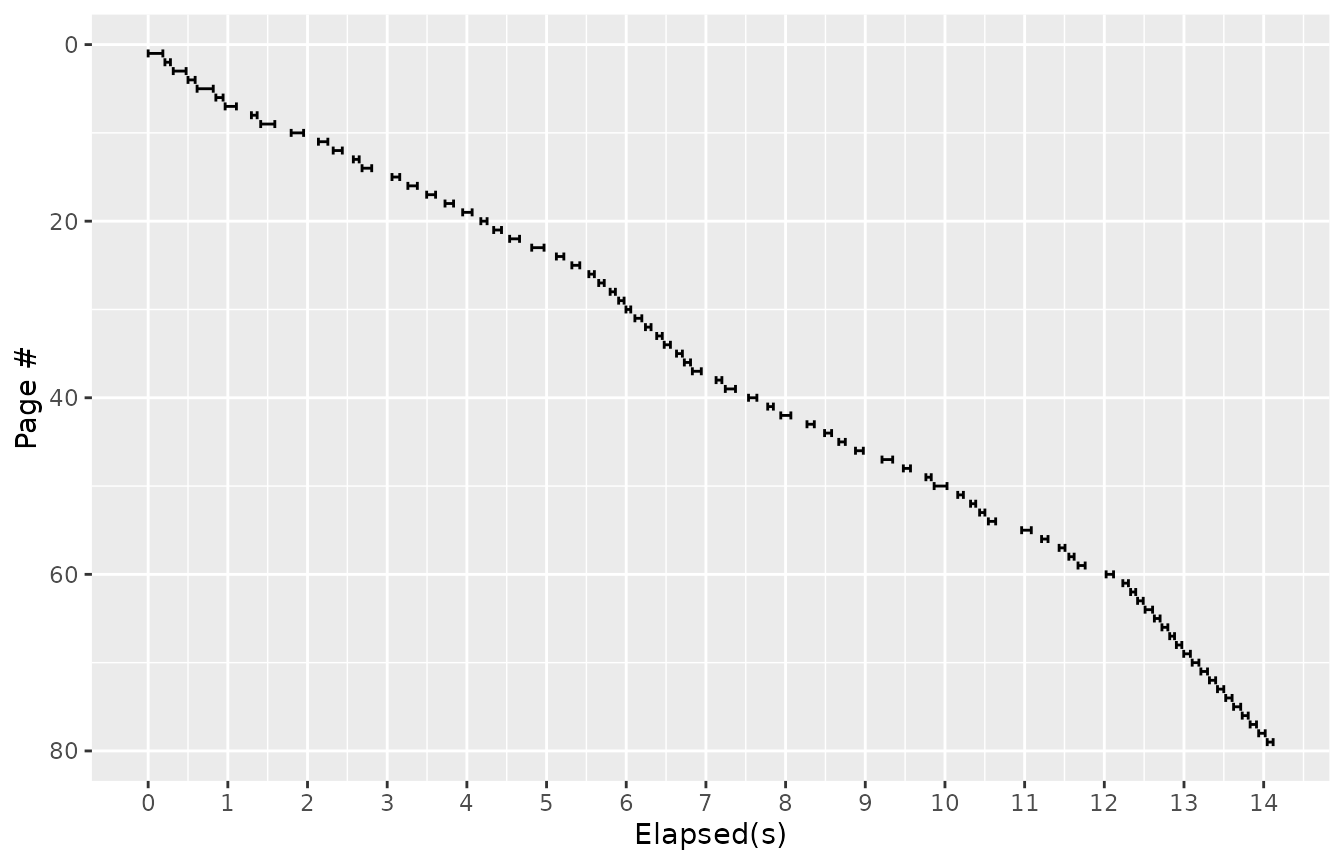

Along the way we recorded “start” and “end” times, before we sent the request and after we received the results. So we can visualize the time course of our web spidering thus:

library(ggplot2)

time_plot <- function(results) (

ggplot(results)

+ aes(xmin=start-min(start), xmax=end-min(start), y=rank(start))

+ scale_x_continuous("Elapsed(s)", breaks=0:16, minor_breaks=seq(0, 16, by=0.5))

+ scale_y_reverse("Page #")

+ geom_errorbarh()

)

time_plot(spidered)

Most of this time is spent waiting on the inherent latencies of the

network, rather than using the local CPU for anything. Latency can

become a bottleneck limiting the performance of any application that

relies on other servers. In this test

R (curl.time / elapsed.time)*100% of the time is spent

waiting for curl. The remainder of the time is spent on

parsing the HTML and extracting links.

Concurrent connections?

For this reason, it would save a lot of time spent waiting if we

could be working on more than one connection at a time. In fact, package

curl does have a sort of asynchronous interface that allows

it to use multiple connections. You can request a page with

curl_fetch_multi(url, done, fail), which accepts a pair of

callbacks for normal or error return values. Behind the scenes,

libcurl maintains a connection pool and can keep track of

multiple pending requests.

After you call curl_fetch_multi, at some point in the

future it will call the done or fail. There is

a catch, though: You need to periodically call

curl::multi_run to allow libcurl to do its

thing. Because libcurl does not run in a separate process;

it only does anything when R calls it. When you call

curl_fetch_multi curl will add your request to a queue, but

you need to call multi_run for it to perform the next steps

– sending, receiving, and assembling the received data.

So, to use concurrent connections, the above program could be rewritten to. To sketch it out:

-

visit_pageneeds to have inner functions, sayprocess_pageandprocess_error, to serve as callbacks. -

spider_sitewould need to be built around a loop that callsmulti_rununtil all pages have been downloaded, rather than a recursive function.

This would amount to some restructuring of our program. But rather

than rewrite the whole logical flow of our spider, there’s a way to

abstract away most of the needed changes, That’s where the

async package comes in.

Wiring up curl to promises

Lots of software supporting asynchronous processing does so with an

ad-hoc API; here libcurl uses curl_fetch_multi

and multi_run. The async package relies on the

promise class, from package “promises,” as a unifying

abstraction for asynchronous requests. To use an ad hoc asynchronous API

with the async package, the first step is often to make a

shim presenting that API in terms of promises.

Here is a function which accomplishes that:

library(later)

library(promises)

# global variable

curl_is_active <- FALSE

curl_fetch_async <- function(url) {

# Promise constructor provides two callback functions

# which fit right in curl_fetch_multi's arguments

pr <- promise(function(resolve, reject) {

curl_fetch_multi(url, done=resolve, fail=reject)

# since we've just told curl to do something new, let it start

multi_run(timeout = 0, poll = TRUE)

})

# And then start checking it periodically

if (!curl_is_active) {

curl_is_active <<- TRUE

later(poll_curl)

}

pr

}The first part of curl_fetch_async is straightforward:

we call the promise constructor, which gives us two

callback functions resolve, and reject, that

plug right in to the arguments for curl_fetch_multi. So the

promise object is constructed that will represent the

pending page download.

Calling curl_fetch_multi just adds our request to

libcurl’s queue; The rest of the function has to do with arranging to

call multi_run, where libcurl actually does

its work. We call multi_run once after adding the request,

to allow it to start opening a connection. After creating the promise,

we check a global flag and if not set we call

later(poll_curl). What this does is to arrange for

poll_curl (defined below) to be called later, in R’s event

loop.

The event loop

R’s event loop runs while R is otherwise idle or awaiting input. R enters the event loop when it is waiting for the user to give input at the prompt; in the event loop R repeatedly checks for keyboard input as well as other things, like network connections or GUI events.

For example, the builtin HTTP server help.start() uses

the event loop; when it is active the event loop will periodically check

for and handle incoming HTTP connections. The Shiny web server also does

this. When a graphics window is open, the event loop is where R checks

for mouse clicks or window resizes. And the promises

package, and by extension async uses the event loop to

schedule processing.

The later package

provides a simple interface for us to to use R’s event loop to check in

things. Above, in curl_fetch_async we called

later(poll_curl), which arranges for poll_curl

to be called on the next run through R’s event loop. Here is the

definition of poll_curl:

poll_curl <- function() {

if (length(multi_list()) == 0) {

curl_is_active <<- FALSE

} else {

multi_run(timeout = 0.001, poll = TRUE)

later(poll_curl)

}

}This calls curl’s multi_run which, given

poll=TRUE will do what it’s been tasked with – opening,

sending requests, and reading whatever data has been received. We give a

short timeout in case something else wants to use the event loop. And

finally we use later to do this again the next time through

the loop.

The global flag curl_is_active is used to keep from

cluttering up the event loop with multiple concurrent checks, and to

make sure we stop polling curl once all requests have been

filled.

An Asynchronous Spider

Interfacing curl with async was the hard

part. Now that this is accomplished, we can make our web spider operate

concurrently. Here is the asynchronous version of our web spider:

library(async)

spider_site_async <- async(function(

start_pages, #starting URLs

regexp, # Linked URLs must match this to be included

limit=500) { # maximum number of pages to collect

#all encountered pages will be collected in this hash table

pages <- new.env()

# keep track of how many URLS seen and stop after a limit

seen <- 0

# inner helper function:

is_new_page <- function(url) {

is_new <- (seen < limit) && !exists(url, pages) && grepl(regexp, url)

if (is_new) {

#mark this page as "in progress" and increment counter

pages[[url]] <<- list()

seen <<- seen + 1

}

is_new

}

# define inner recursive function to visit a page

visit_page <- async(function(url) {

cat("visiting (async) ", url, "\n")

# Fetch the page

start_time <- Sys.time()

data <- curl_fetch_async(url) |> await()

end_time <- Sys.time()

# extract the links and store our page in the hash table.

links <- extract_links(data) |> unique()

pages[[url]] <- data.frame(

url = url, start = start_time, end = end_time, links = I(list(links)))

#recursively follow new links, if within the site filter

( links

|> Filter(f=is_new_page)

|> lapply(visit_page)

|> promise_all(.list=_)

|> await())

invisible(NULL)

})

# Kick off by visiting each page in the starting set.

start_pages |> lapply(visit_page) |> promise_all(.list=_) |> await()

#Return our hash table as a data frame with "links" as a list-column.

pages |> as.list() |> do.call(what=rbind)

})For the most part, this is almost identical to the non-asynchronous version. In fact the only differences are:

- Function definitions for

spider_siteandvisit_pageare both wrapped inasync. - The call to

curl_fetch_memory()is replaced bycurl_fetch_async(url)(which we defined above) followed byawait(). - Both calls to

lapply(visit_page)are followed by|> promise_all(.list=_) |> await().

Wrapping a function definition in async creates an async

function. This is effectively a function that can pause and resume.

Calling an async function does not execute the function immediately, but

returns a promise, that will be resolved with the function’s eventual

return value. The function will actually begin executing the next time R

runs the event loop.

When an async function reaches a call to await(x), it

pauses, allowing R’s event loop to continue. The argument to

await should be a promise.

After that promise resolves, the awaiting function will then resume with

that value.

A single thread, dividing attention between tasks

To unpack the phrase

lapply(visit_page) |> promise_all() |> await(): As

visit_page is now an async function,

lapply(visit_page) will create a list of promises.

promise_all()

combines them into one promise. The await() then causes the

outer function to pause and return to the event loop. In total, this

phrase means to make several asynchronous calls to

visit_page, then pause until all of those calls have

resolved. Effectively, this makes several concurrent calls to

visit_page.

When the outer function pauses, R will then be free to move to the

next task in the event loop, namely to start running the first of those

visit_page calls. It calls curl_fetch_async

and pauses, causing a new task is added to the queue: call

poll_curl. Each of the other calls to

visit_page do so in turn.

Then the event loop gets to poll_curl, which calls

multi_run which finally allows libcurl to get to work,

opening connections and sending requests. When the first received page

is complete, curl_fetch_async’s promise resolves, allowing

the calling visit_page to resume; it now can run and

extract the links from the page. Having done so, it adds a few more

visit_page calls to the event queue, and so on we go

recursively.

The effect is, our concurrent spider is doing everything the

non-concurrent one did, in the same logical order, given that

the code is nearly the same and all, but in a different

temporal order. Putting a few await calls here and

there allowed the task to be divided up in pieces that could run without

waiting on each other.

You can view the way we are using async functions and event loop here as a form of “cooperative” multitasking; dividing a single thread’s attention across several concerns.

How does it run?

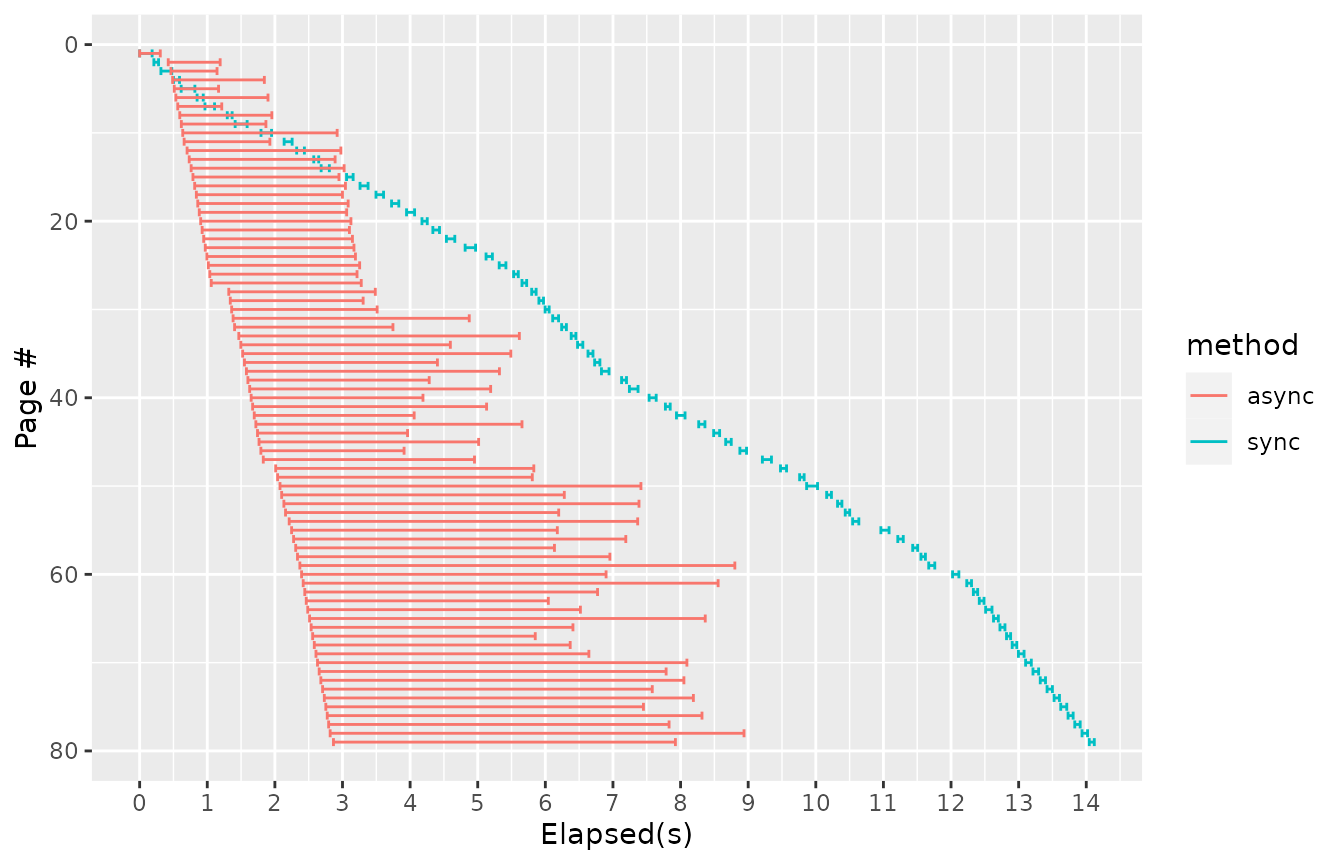

As we have recorded a timestamp when we start and finish each request, we can illustrate the difference in performance.

Now let’s compare the asynchronous and synchronous versions of the same pipeline.

spidered <- spider_site("https://mysite.example/webapp", "mysite\\.example/")

spidered_async |> then(\(x) x |> saveRDS("spidered_async.rds"))(Again, the above isn’t run in the vignette; here’s a precomputed test file.)

spidered_async_data <- readRDS("spidered_async.rds")Let’s look at the elapsed time for both runs on the same chart:

spidered <- (spidered

|> mutate(method="sync", order=rank(start),

end=end-min(start), start=start-min(start)))

spidered_async_data <- (spidered_async_data

|> mutate(method="async", order=rank(start),

end=end-min(start), start=start-min(start)))

(rbind(spidered, spidered_async_data)

|> time_plot()

+ aes(y=order, color=method))

We can see that in the asynchronous version, page requests overlap;

one page does not have to be received and processed for it to start

working on the next. This allows for there to be several requests “in

the air” at any one time. The pages are processed and links are

extracted as the results come back. Concurrency allows the whole task to

be done quicker. As a side effect, any individual request takes longer

to be completed; Increasing throughput with concurrency often does have

the effect of increasing the latency for any one element of data to be

processed. Much of the latency between start and

end is actually accounted for by the request waiting in

licurl’s queue, as libcurl has a sensible default maximum of 6

concurrent connections for a single host.

Conclusion

The async/await construct helps a

single-threaded R process to interact with a concurrent world. Using

async, your programs can have a familiar sequential

structure, but multiple async functions can run concurrently as process

data as it becomes available. This means your program can spend less

time waiting and more time processing.